January 28, 2018

“A Brown-Eyed Handsome Man”

My wife Amy’s father--Seymour Irving Gussack--universally known as Gus or Papa—passed away in his sleep last Wednesday morning, January 17, six weeks after his 94th birthday party. He finished his memoir, entitled Incidents & Coincidence, just in time for his party, where he had the pleasure of signing his book for all his friends and family. In the memoir, which was written in collaboration with professional memoirist Nancy Kessler, Gus modestly emphasizes the incidental quality of his achievements, which he characterizes as dependent more on serendipity and chance than on the energy and hard work that he put into everything he undertook. Incidentally, after the fact, we discovered that, as coincidence would have it, the published book was exactly 94 pages long!

The cover of Gus' memoir

As his memoir reveals, Gus was a most unusual man. He played a number of different but related roles in his life: entrepreneur, industrialist, world traveler, advocate of international trade, a die-hard Yankees fan who almost became a Major League catcher and who, while playing fantasy-camp baseball at the age of 80, got a base hit off the formidable and notoriously intimidating Hall-of- Fame pitcher, Bob Gibson. Gus was also a Cold War covert agent for the CIA, and, not least, in the words of Chuck Berry, he was “a brown-eyed, handsome man.” His good looks undoubtedly had something to do with his winning the heart of his beautiful wife, Manya Kanof, and with initiating his 23-year-old romance with Ellen Wiesenthal, his long-time fiancée.

Highlights from his working life include placing his company General Bearing in the forefront of American businesses to open Japan and China to Western trade and his pursuit of business relations with former Soviet satellite countries in Eastern Europe. At the same time, he was investing in a small lobster business consisting of a boat, a dozen lobster traps, and two local fishermen on the Caribbean island of St. Maarten, a favorite family winter vacation spot, as well as treating his family to extended summer vacations on Cape Cod, eventually buying a house on Great Pond in Eastham for the use of the whole Gussack family—a venture that he considered his greatest and most satisfying achievement.

It’s true that Gus always had more than his share of ego, but he also had more than his share of friends. He was ambitious without being self-promoting, exceptionally intelligent without being arrogant, an unusually modest and generous man and a loyal friend who not only always took the check but who, more than once, gave me not only the shirt but the leather jacket off his back, and who ascribed his success in life to nothing more than chance and synchronicity. If one’s death can ever be said to be lucky, Gus’s death certainly was. He died in his own bed with Ellen lying beside him, and death came swiftly and yet with enough warning that we were able to be there with him at the end to hold his hand and kiss him goodbye.

Gus was buried two days later with military honors that included a lone bugler playing Taps at his gravesite, as he had requested. His memorial service was more a joyous celebration of his life than a mourning of his death, and it included the reading of a letter that Gus had written thanking his rabbi for reminding him of the Yahrzeit anniversary of his mother’s death. Gus’s letter, which is reprinted in his memoir, expresses the private, spiritual essence of him more powerfully than anything my words might say:

Dear Rabbi Weinberger,

Thank you for the letters reminding us of the Yahrzeit of our loved ones.

It has been a most difficult year and the struggle to stay afloat has fully occupied both body and mind. So I was surprised to receive your note reminding me of my mother’s Yahrzeit—another year could not have passed so quickly. Yahrzeit has always been a deeply moving period for me, but my feelings and my memories have always remained with me, unshared with the outside world. I want to share my feelings with you in appreciation of the reminder.

The lighting and the burning of the candle in memoriam is a mystical experience. Year after year as the candle burns for my mother or father, I focus intensely on my memories of them. I can see and hear them again clearly, almost making contact.

My mind’s eye returns to many years past and I can see my parents lighting the candles for their parents. In this state of concentrated thought and recollection, one can see that our people are represented by that endless string of candles stretching back, who knows how far.

The candle burns on, sometimes brighter, sometimes weakly, like life itself. And then--it’s out—like life itself.

Eventually I’ll be represented by a light in my children’s homes, another in the endless path of tradition. It must be tradition after all that keeps the fiddler on the roof.

Again, I thank you for the reminder and the prayers at Anshe Sholom. I wish you and your family all the best in health and peace.

With warmest regards,

Seymour Gussack

January 10, 2018

A Great Artist You've Probably Never Heard Of

Jim Youngerman, Untitled, mixed media on paper

I want to introduce you to my friend, Jim Youngerman, and also to his wonderful website. Jim is an artist whose paintings and drawings you’re probably unfamiliar with, but now with the Internet and the opportunity to create your own individual website, it’s possible for Jim and other artists and writers (like myself) to find an audience for their work without relying on galleries and museums (or literary magazines) to display it. Jim and his wife, Jane Goodrich, an incandescent professional dancer, live in Lenox, Massachusetts, in the Berkshires, all the way across the state from us, but we manage to get together frequently nevertheless because Jim and Jane love the Cape as much as we do. We first met Jim ten years ago when Amy and I hired him to renovate our house on Cape Cod, and I discovered that, besides being an exemplary carpenter by day, Jim Youngerman is an accomplished artist by night. Jim has to have a day job because he can’t make a living from his art alone, any more than a poet can. This despite the fact that I would go so far as to call Jim a truly great artist, a unique and consummate original, an artist whose paintings and drawings are as arresting and as engaging as the work of any artist of our time.

Jim lives in the same place where Norman Rockwell lived while he painted his famous idealized—some would say sappy—portrayals of American life as cover art for over 300 issues of The Saturday Evening Post as well as for many other magazines. It seems unfair that, despite the clichéd sentimentality of so much of his work, everybody has heard of Norman Rockwell, while Jim Youngerman, a deeply serious artist of enormous talent, goes largely unknown. I’m writing this now as if I could correct the imbalance of Rockwell’s popular fame and Jim’s relative obscurity, though it’s highly unlikely that my blog could ever have such a far-reaching and salutary effect.

Pause, from Jim Youngerman's "Shadow Series"

Despite the neighborly proximity of their mutual location in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Jim and Norman are very different kinds of artists. Norman Rockwell is generally considered a commercial illustrator rather than a serious painter, and you might call Jim an anti-Rockwell artist because rather than painting nostalgic representational portraits of ordinary people engaged in iconic middle-class pursuits, Jim paints highly imaginative, cartoon-like pictures that are ironic, mysterious, humorous, and strange. Another difference is that, whereas Norman Rockwell planned out and rehearsed every detail to suit the theme he wanted to express in a particular painting, Jim’s work depends more on intuition and accident than on conscious intention.

Youngerman's pictures are ironic, mysterious, humorous, and strange. (Untitled, watercolor and pencil on paper)

Jim takes a free-associational, stream-of-consciousness approach to his material. He says he uses “simple lines in a lyrical, figurative, quasi-cartoon style in order to understand and illuminate different levels of awareness and consciousness” in himself. For instance, in the untitled post-Surrealist painting that opens Jim’s website, we encounter drawings of three tusked rhinoceros heads, five naked dancing girls wearing clownish masks, three sailing sloops with triangular white sails, three stiletto heeled shoes, and a mirrored image of ten silhouetted figures standing in front of two windows, or maybe paintings, making for a dualism of reality and artifice that is self-reflexive in the manner of post-Modernism, underscoring the subjective relativism of truth and the artificiality of artistic forms through an insistence on symmetry, mirror-imaging, and accidental patterning. It’s not surprising that Jim’s work is also often experimental, as for instance his collaboration with the award-winning poet and translator, David Keplinger to make a set of drawings called “Transparencies” that melds Jim’s visual imagery with fragmented lines from David’s poems.

From Youngerman's "Transparencies," which use language from Keplinger's poetry

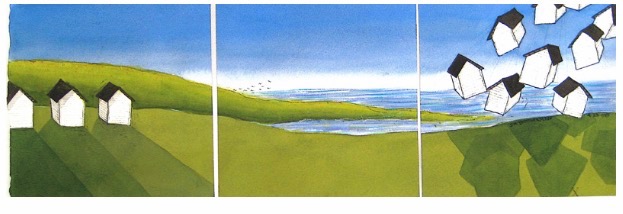

But I’m just scratching the surface of the variety and richness of Jim Youngerman’s work, which includes architectural images of doorways and archways that could be paintings or, just as easily, windows looking out on bodies of water or city streets, And it includes floating little Cape Cod saltbox houses in triptychs of what he calls, “Lonesome Landscapes,” and mirror-image black-and-white silhouettes of cowboys and umbrellas and crows and porcupines, as well as segmented paintings (like the one previously described) that contain a Surreal array of stand-alone or boxed images.

A 1995 untitled tryptich from Youngerman's "Lonesome Landscapes" series

It may be that Jim is fated to be one of those painters or writers whose genius was only fully recognized after they were gone, as was the case with Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, but my hope is that the Internet will keep Jim Youngerman’s gorgeous work alive and his name will not be added to that sad list of artists who went unrecognized (or under-recognized) during their lives.

To get a sharper sense of the inexpressible richness and originality of Jim Youngerman’s work, you merely have to visit his website. I promise that you will be enormously impressed, and quite possibly amazed, by the work you discover there.

January 1, 2018

A walk through Caledonia State Park, PA, in June 2017. My family has shared a log cabin here for over 70 years.

CALEDONIA POEMS

These eight poems form a memoir of childhood summers at the Moyer family’s log cabin in Caledonia State Park, Pennsylvania

C. D.’S FISHING

My grandfather holds a fishing rod

and carries a wicker creel against his hip.

Behind him, the leaves of summer are

an unfocused dazzle. Because he was

Trainmaster for the Reading Railroad,

after he died, my grandmother rode on

a pass as his widow—which she was,

though she was always her own woman

first: the eye she watched the fields

slip past her window with was just

as incisive as the hooks he’d hide in

the feathery lures he liked to tie on

winter nights while he’d wait the coming

of the thaw and his return to the trout

streams. He gave my grandmother ten

children, nine of whom lived. When he

couldn’t fish, he’d walk the woods

of the golf course and pick up lost

balls, like fabulous white mushrooms

from the shadows beneath skunk cabbage

and from creek-bed nests of maidenhair.

THE INSIDE OUT

We were in my grandfather’s old Studebaker

on our way to the mountains for the summer

and already in thick woods when it happened.

I hardly even felt it, just a bump in the road,

but my grandfather pulled over and stopped.

It was a big gray squirrel with its fur unmarked,

and my grandfather held it toward us like a bowl

of something he didn’t want to spill. Caught it

with our bumper, he said. Then he put it inside

the trunk, and we drove on through the blinking

sunlight. When we got to the cabin, I saw what

he had up his sleeve. Out back by the pump, he

took the pocketknife I’d seen him pare apples with,

unwinding the peel in one red ribbon, and split

the belly open. Then he showed me what was in

side, unfolding each organ one by one, giving me

the heart to hold in my hand, unraveling the blue

intestines. We tacked the hide to a board, raw

side out and salted, and put it out in the sun

because my grandfather said that would cure it.

KICK THE CAN

Running down a narrow path, in the woods

in back of the cabin, ducking the tickle

of spider webs, deeper into the dark, I

evade the reach of sucker vines and drop

to the ground, my arms shielding my head:

roll under the perfumed skirt of a spruce

to my hide-out’s cushioned floor: lie there

suspended, caching my breath, then sit cross-

legged and still: count time by the stitches

the fire-flies make in this feathery screen

of fir: wait until everyone’s caught but me

and there’s no one else left who can save them.

IN COLD WATER

We must’ve gone swimming like dancing,

to touch, because outside the water

we never did: she was years older,

and, besides, I thought incest applied

to cousins. But we’d meet underwater,

summer afternoons, after the same object,

a smooth stone or maybe a bright skeleton

key we’d throw and dive for, bug-eyed

and goose-bumped, grappling for it, her

legs twisting around my hips or even

my neck, staying under until we almost

burst, then exploding into the noisy sun

light, gulping air, flinging off water

like sparks—spring-cold, it could turn

your lips blue, but we never wanted

to come out once we got used to it.

GETTING TO THE INN

My cousins and I would rebuild the stone

dam across the creek early in the summer.

Every night after dinner we liked to dance

to the jukebox and rock in the rocking

chairs or lean against the railing logs

of the Inn porch, rattling the crushed

ice in our Cokes and trying to look cool.

Up to our crotches in cold creek water,

we’d pave our way there, wobbling across

the rocky bottom to shift big, submerged

boulders through the current and sliding

smaller ones into the slippery cracks

between, until a stony spine would arch

its way to the opposite side. It was solid

if you knew the special combination

of steps that would hold your weight

but shaky enough to get our feet wet

the first couple of times we tried it.

O HOLY NIGHT

Slipping out of the sleeping porch, we carry flash

lights, Jack and I, but we don’t turn them on yet.

In case someone looks out, we feel our way over

pine roots through shadow, as sly as diamond thieves

pulling off a heist. Our faces glow like stones

in the moonlight and seem to float in the dark above

the path to the tourist camp, where the girls are

waiting, camped out with no chaperone at long last.

They are sitting in the circle of their own fire

light, their voices rising and falling like our own

breathing, as we come up to them through the trees.

We know how to pair off but we don’t know where

to begin, so we walk up to the golf course to look

at the stars. The fairways are milky with dew,

and our sneakers make tracks across the dark greens.

Here, I move like a sleepwalker holding her hand,

until finally she’s the one who releases me with

a kiss, her mouth opening to offer some heavenly

gift of tongues that descends from on high as we

sink into the sand trap at the seventeenth hole.

HITCHING IN THE SUMMER

From Caledonia State Park to the Gettysburg

Battlefield, the Lincoln Highway runs through

green Appalachian mountains with pines and then

orchards on their slopes, on down into fields

of corn or Queen Anne’s Lace, where it widens

to three shadowless lanes before narrowing to

a tarred and shady two and running across a creek

beside a Mail Pouch barnside, then by a cemetery

and on into town. Fifteen miles can stretch

into a lifetime, and you can feel married for

keeps to what you happen to see from the cable

guardrail, there by the road, where you sit raising

your arm to the cars, each one coming slowly

then rushing away, leaving nothing behind but

an upstart of dust and air, and you, balancing

on a tight wire over this landscape you are

a stranger in: the checkerboard of orchards

on the blue hills: the hum of a bee hovering

above a flat circle of tiny white flowers

fanned out no wider than the palm of your hand.

THE CHURCH IN THE WILDWOOD

One night in the mountains, lightning struck

the oak that held the bell my grandmother

rang each Sunday morning all summer long

to call the tourist camp to worship under

the pines. When the oak split, the bell

stayed put, but half the tree fell on our

neighbor’s front porch. The roof caved in

and Rev. Manges might have called it a

judgment if the roof hadn’t been his. God’s

ways were mysterious, my grandmother said,

and we watched Rev. Manges spend the rest

of July chopping that oak tree to pieces. He

burned all the leafy trash one night in a great

bonfire with the shadows dancing like wild

Indians on the warpath at a Saturday matinee.

Where I live now, there are two white oaks right

next to the house and a tall Colorado blue spruce,

so when the sky darkens early late on a summer’s

day, I sit on my porch sipping vodka and wait

for the show—or the savage kingdom to come.

December 1, 2017

The Great American Movie: On McCabe & Mrs. Miller

Beatty with Altman (right) on the set of McCabe & Mrs. Miller

For years I’ve said that my all-time favorite movie is a film directed by Robert Altman called, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, starring Warren Beatty and Julie Christie. It’s a movie that I fell in love with during my first breathless viewing of it, which was at The Cinema Theater in Chevy Chase, Maryland, soon after the movie’s release in August, 1971. The movie catches you even before it begins with the rushing sound of a strong wind blowing, and then it opens with a long shot of green trees, a mountain forest through which we see a single rider wearing an oversized fur coat and leading a second horse laden with saddlebags and what turns out to be a hat box. As the rider approaches, Leonard Cohen’s “Stranger Song” plays on the soundtrack and Cohen’s voice seems to characterize the lone rider as a stranger and a gambler on a quest:

It’s true that all the men you knew were dealers

who said they were through with dealing

every time you gave them shelter

I know that kind of man

It’s hard to hold the hand of anyone

Who is reaching for the sky just to surrender.

Like any dealer he was watching for the card

that is so high and wild

he’ll never need to deal another.

He was just some Joseph looking for a manger.

He was just some Joseph looking for a manger.

The words of the song seem to mythicize the stranger, who turns out to be McCabe, as he is juxtaposed next to the spire of a church that’s still under construction. It’s very telling that the first thing we see McCabe do when he arrives at this little zinc-mining frontier town-in-the-making (it was filmed in Vancouver) with the loaded name of “Presbyterian Church,” is to struggle out of his great fur coat and to take a Derby hat out of its hat box on the horse he’s been leading and to settle it carefully on his head. Now, as he rides into town, he’s got his front in place, and he occasionally smiles and tips his hat to people as he passes. The town has muddy dirt roads and there’s a makeshift rope bridge over a small stream to a shanty with a sign identifying it as Sheehan’s Saloon & Hotel. There’s a long shot of McCabe standing at the entrance to the bridge and lighting a cigar; the cigar smoke rises above his shoulders as Cohen’s voice sings:

Ah you hate to see another tired man

lay down his hand like he was giving up the holy game of poker

And while he talks his dreams to sleep

you notice there’s a highway

that is curling up like smoke above his shoulder.

It’s curling up like smoke above his shoulder.

At some point during that first murky-green, smoke-dark interior scene in Sheehan’s saloon that follows, I knew that this was the real thing, and the feeling only deepened as the movie went on. I felt drawn in and somehow made expectant by the way the dimly lit, shadowy interior of the saloon is suddenly cut through and illuminated when Sheehan lights the oil lantern suspended over the poker table that McCabe has just covered with a red baize tablecloth. The lantern light falls across that tablecloth and lends to the faces of the players sitting around the table a warm sepia tint. The faces have an individual quality and the men’s voices naturalistically overlap and words are indistinct. The warm yellowish-brown quality of the light is recalled in a later scene when the five newly arrived whores, Mrs. Miller’s so-called “beautiful ladies,” bathe together in the two great wooden bathhouse tubs, and their skin takes on a warm antique glow from the fire that heats the water. Before he crosses the. make-shift rope bridge to Sheehan’s Saloon, McCabe lights one of his cigars. The Derby hat, the cigar, the gold tooth that appears when he smiles, the neatly trimmed beard, the bear-fur coat, and even the ostentation of cracking a raw egg into his glass of whiskey--it’s all part of the persona he is creating for himself, an image of the dazzling fellow he’s trying to be. The idea that he has worked at constructing his façade seems to be corroborated by the fact that he used to be called “Pudgy” McCabe. Like Jay Gatsby in what I think of as the great American novel (and like America itself), McCabe might also be said to spring “from his Platonic conception of himself” in the sense that he is fathered by an abstract and ideal self-image-- which is what is meant, I think, when Gatsby is called “a son of God”; similarly, Leonard Cohen’s lyrics on the soundtrack identify McCabe as “just some Joseph looking for as manger,” words we hear in the opening and that are repeated as we see a close-up of McCabe, newly arrived, looking through a window into Sheehan’s Saloon and Hotel.

When the movie was over, my first response was immediately to see it again. I had always been an inveterate movie-goer with fairly catholic tastes, but for a good while McCabe & Mrs. Miller spoiled me for other movies. My contention has always been that the main reason the movie had such an impact on me was simply because, objectively and esthetically speaking, it’s a great film—by which I mean I would put it in the company of my most prized movies, movies that would include Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Jules & Jim; Howard Hawks’ Red River and His Girl Friday; Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane; John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre; Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, and David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia.

But reasonable as my adulatory response to the movie might have been, I also knew that my high regard for the film had something to do with my fixation on--and identification with--the image of the “beautiful loser”—that is, the sensitive-but-doomed artist-hero, the archetype of whom must be Orpheus, the fabulous musician of Greek myth (son of Apollo and the Muse Calliope) who played the lyre and sang so beautifully that, in the words of Edith Hamilton, “He moved rocks on the hillside and turned the courses of rivers . . . No one and nothing could resist him.”

Although he may not be a musician, McCabe is nevertheless a charismatic artist of sorts--in fact, for me, McCabe is a homespun American version of the mythical Orphic loser. McCabe himself declares that he’s a kind of frustrated poet. As he’s preparing to go into the nearby town of Bearpaw to try to make the deal with Harrison & Shaughnessy Mining Co. in order to keep himself from getting killed, McCabe talks to himself (as he has a habit of doing) about the depth of his feeling for his Eurydice, Mrs. Miller (her first name, ironically, is ”Constance”): “I take a look at you sometimes and I just keep a-lookin’ and a-lookin’. . . and sometimes I want to feel your little body up against mine so bad I think I’m gonna bust . . . I keep tryin’ to tell you in a lot of different ways.” And then he says, “I’ll tell you something, I got poetry in me! I do! I got poetry in me. But I’m not gonna put it down on paper—I ain’t no educated man—I got sense enough not to try it.”

I’ve owned a DVD of McCabe & Mrs. Miller ever since it became available. In recent years, of course, computer technology has enabled us to look at a film on tape or disk as many times as we want to. So yeah, I own a copy of McCabe, but as a consequence of its easy availability and the fact that its shrunken video form reduces its visual presence to the dimensions of a computer monitor or a TV screen, a certain amount of the movie’s power to enthrall has been muted. In a way, my experience of the film in this new form and these new circumstances, feels more like my experience of prose---more detached and observational than the passionate, overwhelmed feeling I had when I saw the movie in the theater.

Watching McCabe & Mrs. Miller on DVD, I become as absorbed as I am re-reading The Great Gatsby, It’s the feeling of being in the presence of art--that is, it gives the sense of being highly artificial and yet hyper-naturalistic at the same time. It seems true-to-life in a way that other movies, in comparison, do not. It seems to me, in its textures, and in its diffuse, interwoven visual style, to be unprecedented, truly original. Eventually, I came to learn that Altman achieved this sensation of verisimilitude very purposefully and consciously through such devices and strategies as using multiple microphones and soundtracks, allowing the actors to improvise and encouraging collaboration, using natural light, flashing the negative of the film to give it an antique, sepia look, filming the scenes in the actual sequence they would have in the movie, and perhaps most of all, turning a scene into a real event and then filming it documentary style, as for instance actually building the town of Presbyterian Church in reality and using the buildings that were being constructed as the movie’s set.

In my case, the experience had something to do, I think, with my seeing McCabe as the American Dreamer, the prototypal American Innocent, a beautiful failure destroyed by the very values that shaped the terms of his self-creation. What is indicted in the movie is the ruthless corporate greed that seems endemic to the American business world. If McCabe is a poet manqué, he is also, so he insists to Sheehan, a “businessman, businessman,” and it’s as such that he resembles the frog that he likes to say bumps its ass so much because it doesn’t have wings as well as the little frog that gets swallowed by the eagle in the joke that McCabe tells the two corporate deal-makers sent by Harrison & Shaughnessy Mining Company to buy him out. Of course, the joke is on McCabe: he shares the unhappy fate of both frogs. The American free-enterprise system--which is what has guided McCabe’s effort to become successful--is corrupt at the core, and McCabe’s impersonation of the successful entrepreneur he aspires to be and likes to think he has actually already become is mere veneer and cannot keep him safe when he runs afoul of the mining company that wants to buy him out. What he aspires to be is a gentleman of property, and that’s what he believes he’s on the verge of becoming; it’s what leads him into the mistaken assumption that he can bargain with Harrison & Shaughnessy. It’s his impersonation of quality that Mrs. Miller mocks when, shortly after they meet, she tells him, “If you want to make out like you’re such a fancy dude, you ought to wear something besides that that cheap Jockey Club cologne.”

The original title of the movie was “The Presbyterian Church Wager.” The name of the town seems loaded to suggest America’s Calvinist roots and to make the town a synecdoche of America itself. The church that is being built, however lovely from a distance, is a cruel and heartless place with a hell-obsessed minister who is associated with images of fire throughout in contrast to the saloon-and-bathhouse-brothel that McCabe builds and that could be said to become the true heart of the town. The remarkable scene in which the five “Sisters of Mercy” bathe naked in the golden light of the fire that heats the bath water in McCabe’s newly constructed bathhouse, laughing and splashing in the water and singing “Beautiful Dreamer”—contains images that seem to express the human warmth and even spiritual nourishment that the saloon-bathhouse-brothel provides and represents It’s characteristic of Altman’s iconoclastic, subversive approach to traditional film genres that his hero is a saloon owner, someone who would have typically been a villain in a traditional Western; also that the realistic shootout is far from the typical Western duel in the middle of the street.

The whole climactic stalking shootout, which takes place in the falling snow, is extraordinarily beautiful—and silent—it’s early in the morning, and the only sounds are the crowing of a rooster, the barking of a dog, and the crunch of McCabe’s boots in the new-fallen snow. The snow fall was real—it came as an accident that Altman took advantage of rather than allowing it to impede the filming. McCabe breaks with Western tradition by managing to shoot two of the hired killers in the back (the half-breed and the “Dutch boy” who shot Keith Carradine’s innocent cowboy in cold blood), and he outdoes himself when he shoots Butler, the biggest and bad-est of the killers, right between the eyes with a derringer. But McCabe has been fatally shot too, and as he lies hunched over in a drift of snow next to his saloon and becomes gradually unrecognizable under the growing mound of snow, the town’s people--unaware that McCabe, who is arguably the true heart of the town, is dying--come together to put out the fire in the church. The cross-cutting between the community’s successful effort to save the church and McCabe’s unsuccessful effort to stay alive makes for a concluding irony that is as tragic as it is ironic.

Playing the cynical realist to McCabe’s hopeful romantic, Mrs. Miller sees through McCabe’s posturing from the outset. And I think she also sees that he’s a star-crossed and unlucky gambler who is doomed to lose. This is why she tries to keep McCabe at a safe emotional distance (making him pay to sleep with her like anyone else). She’s trying not to care about him too much, because she figures that, given his essential innocence, she’s bound to lose him sooner or later, and it’s best to avoid the pain and narcotize herself with opium, which she purposely does when, alone, McCabe faces the three killers.

The night before the shootout, McCabe breaks down, telling Mrs. Miller that he’s sorry (really telling her he loves her); and she strokes his hair and he falls asleep in her bed. But before the night is over, we watch her leave her room and slowly descend an outside staircase through lightly falling snow, then she walks out onto the bridge, stops and gazes out over a bannister into the darkness, her profile gilded with the light from a nearby window. Finally she turns and walks around the corner of the building, disappearing from view. What gives this sequence its power is that Leonard Cohen’s haunting song, “Winter Lady,” is playing all the while; ending at the moment Mrs. Miller turns the corner. The lyrics of the song seem to reverberate with images we’ve seen on the screen in an evocation that has the mysterious precision of poetry. If McCabe were ever to write poetry, this might be the poem he would write:

Traveling lady stay awhile

until the night is over.

I'm just a station on your way

I know I’m not your lover

Well I lived with a child of snow

When I was a soldier,

And I fought every man for her

Until the nights grew colder.

She used to wear her hair like you

Except when she was sleeping

And then she weave it on a loom

Of smoke and gold and breathing

And why are you so quiet now

Standing there in the doorway?

You chose your journey long before

You came upon this highway.

We don’t see Mrs. Miller again until the last scene of the movie, when we find her in a Chinese opium den, where she lies on a pallet and gazes at a small ceramic snuff bowl that she brings up so close to her eye that the bowl fills the whole screen, like a molten, golden world, a dream world of what the West (and America itself) might be or might have been. It’s that final image that Pauline Kael was referring to when, in her pivotal review for The New Yorker, she famously called McCabe & Mrs. Miller, “a beautiful pipedream of a movie.”

As it happens, Leonard Cohen published a novel in 1966 called Beautiful Losers. That somehow seems appropriate for the composer of all the songs on the soundtrack of McCabe & Mrs. Miller. It’s virtually impossible for me to imagine this movie without those songs, every note and word seems so intimately and intricately tied to what’s on the screen. What’s most amazing is that Altman got the idea of using the songs after he’d finished shooting the movie. He had apparently listened to Cohen’s album, The Songs of Leonard Cohen, over and over again while he was filming That Cold Day in the Park, also filmed in Vancouver about a year-and-a-half before McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Then, after filming McCabe, he was in Paris scouting locations for another film when he heard the Cohen album again and decided then and there that he wanted its songs in his movie. Cohen was reluctant at first to let Altman use the songs (apparently he was one of the few who hadn’t liked M*A*S*H), but when he saw a print of McCabe & Mrs. Miller, he let Altman use the music free of charge.

With the addition of the music the film was finished, but its quality and impact was just beginning to be felt. In fact, when it was first released, it was largely panned. Reviewers complained about their difficulty understanding the dialogue and the crowded quality of its mise-en-scene. Pauline Kael was the first influential critic to see it as an exceptional work of art, but in the years since then it’s been widely recognized as Robert Altman’s and Warren Beatty’s and Julie Christie’s finest work, and the movie, in its use of overlapping dialogue and the slow zoom and a new improvisational kind of realism, has been seen as changing the way movies are made. As much as I can’t help taking McCabe & Mrs. Miller personally, feeling that it was somehow meant peculiarly for me, I also can’t help wanting everyone else to see it and to share my belief that it is--more legitimately than Birth of a Nation and more satisfyingly than either Gone with the Wind or Citizen Kane--that mythological beast, “The Great American Movie.”

November 20, 2017

Me Tarzan

Reprinted from: CRUSH, edited by Dave Singleton and Cathy Alter (William Morrow, 2016)

My infatuation with Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan of the Apes started in the summer of 1955 when I was not quite twelve years old and my family was living on the island of Okinawa, where my mother, my sister and I had come on a military troop ship to meet my Army-officer father, who had come by plane from Korea, where he had spent the past fourteen months. In the preceding year, while my father was away, my sister had managed to lose most of what we called her baby fat, and I had earned a string of straight A’s in school, doing so well, in fact, that my sixth-grade teacher had told my mother that, if we liked, I could be promoted directly to the ninth grade and skip junior high school altogether. But it was an opportunity my father had vetoed as soon as my mother wrote him about it. “He would feel like a freak,” my father had written back. “He would be three years younger than everyone else in his class.” But to acknowledge my academic success, he gave me a book that he thought might appeal to me and that he said might also be something of a challenge since it was clearly intended for adult readers rather than for an eleven-year-old boy. Apparently the first volume in a series, the book was entitled—rather thrillingly, I thought—Tarzan of the Apes. The author had three names, Edgar Rice Burroughs; the book’s copyright date was 1912; and although I could see from the first words that reading its verbose nineteenth-century prose wasn’t going to be easy, I was sure that with a dictionary and a little effort, I’d be able to make my way through it. I very quickly discovered that, if anything, the pleasure of reading was only heightened by the concentration that reading such old-fashioned language required.

Tarzan’s African jungle was located on the farthest periphery of the known world—exotic, primitive, and distant—which was one of the things that most attracted me to the book since that was much the way I regarded Okinawa. There may not have been any great apes or lions or gorillas in the grassy fields and woods of the island, but danger lurked nevertheless. There were unexploded hand-grenades and land mines left over from what had been one of the bloodiest battles of World War II, live ammunition that if we came across, we were warned not to even think about touching. We were also told to be on the lookout for the deadly Habu, a venomous snake native to the island that was said to be related to the King Cobra. I carried a pocket snakebite kit to supply first-aid just in case I got bit by one of them whenever I went out “reconnoitering,” as I called my explorations of the surrounding woods and the abandoned cave-like tombs that had mostly been bulldozed to make way for the suburban-style concrete houses with lawns and sidewalks where the dependents of American Army, Air Force, and Marine officers and enlisted men lived. There was no television on Okinawa, and although we occasionally went to a movie on the Base, reading became my chief form of diversion. And imagining myself as Tarzan of the Apes became more than a diversion—it became a refuge and even provided me with what you could call an alternative form of identity.

Whatever its stylistic excesses, Burroughs’s language succeeded in conjuring up for me a hero who embodied everything that I could have wished I might someday become. But the farther into the book—and then into the series of books—I read, the more I began to realize that, even if this heroic version of myself that I yearned to become could only ever exist in my imagination, that might be enough.

Tarzan was described as having a “straight and perfect figure, muscled as the best of the ancient Roman gladiators must have been muscled, and yet with the soft and sinuous curves of a Greek god,” a physique in which “enormous strength wondrously combined with suppleness and speed.” And Tarzan’s inner qualities—his intelligence and his innate sense of justice—were just as significant as his good looks, his physical prowess, and his muscular strength: “With the noble poise of his handsome head upon those broad shoulders, and the fire of life and intelligence in those fine, clear eyes, he might readily have typified some demigod of a wild and warlike bygone people of this ancient forest.”

There was also the animal keenness of his senses (my senses too, at least for as long as I could imagine I was inside his skin). Having such acute senses meant that wherever Tarzan might be, he was intensely there. His olfactory nerves were as sensitive as a bloodhound’s. Burroughs pointed out that because human beings depended largely on their ability to reason, they had let their senses atrophy—but not Tarzan. From early infancy, his survival had depended upon the acuity of his perceptions, so his senses had become preternaturally acute, whereas except when I was inside a story, I was so near-sighted that I sometimes had trouble reading the blackboard at school, and I absolutely refused to wear glasses—after all, would Tarzan ever have worn glasses?

Tarzan’s intelligence was such that it enabled him to teach himself to read English, even though, at the point when he learned to read it, he had never even heard it spoken. Superior intelligence was something I was also beginning to pride myself on, and an innate sense of justice was something that I was sure I possessed too, because I was never in doubt about what was fair and just and what wasn’t, although I realized in later years how blind I had been at the ages of eleven and twelve to the racism and class bias in Burroughs’s treatment of Tarzan’s hereditary gifts. When Tarzan meets Jane Porter, the woman who will become the love of his life, he treats her intuitively with “the grace and dignity of utter unconsciousness of self. It was the hallmark of his aristocratic birth, the natural outcropping of many generations of fine breeding, an hereditary instinct of graciousness which a lifetime of uncouth and savage training and environment could not eradicate.”

It turned out that, like me, Tarzan had two identities: if he was Tarzan of the Apes, he was also John Clayton, Lord Greystoke, and he was defined as much by his aristocratic blood as he was by his feral upbringing and his savage environment. One of my favorite fantasies was that, unbeknownst to everyone around me, I too was actually a foundling prince, and that the couple who were raising me were no more my real parents than Kala, the female ape who adopted the infant Lord Greystoke, was Tarzan’s true mother. Kala had raised Tarzan to be as strong and as self-reliant as he would have to be to survive in the jungle, given his lack of claws and fangs and his pale and furless skin. His name meant White-Skin—a feature that in the jungle put him at a distinct disadvantage. It was thrilling to imagine such complete isolation and vulnerability, and then to watch as this “ugly duckling” turned into a swan to beat all swans. Tarzan of the Apes felt like a scenario for my own ugly-duckling transformation.

I was also struck by the similarity between Tarzan’s displacement to the African jungle where he had been left, alien and alone, both an exile and an orphan, and my displacement to what was called the Far East, where I too felt like an exile and a stranger.

When I discovered there was a volume entitled, The Son of Tarzan, it made me wonder what it might be like to have Tarzan for your father. My father had promised to read that volume with me, but although we knew the book existed, we were never able to locate a copy, so I had to imagine what it might be like on my own. What complicated the fantasy for me was the fact that it was on Okinawa that my father’s drinking became a serious problem. He’d always enjoyed a cocktail or two, but now it got to the point where he was going to bed drunk nearly every night, Tarzan’s virtues—especially his extraordinary self-discipline and the sober rationality of his intelligence—couldn’t help but stand out in bold relief against my father’s slurred words and sappy grin and flushed face. Alcohol seemed to dissolve his native intelligence and make him stupid and sentimental and somehow defenseless. My mother tolerated it, I think, only because it never got so bad that he couldn’t function--and, besides, she sometimes liked to join the party herself. So on a Sunday evening, my sister would crayon or play with her doll collection, my mother and father would sit on the patio and smoke cigarettes and get drunk with their friends, and I would be wherever Tarzan was in the book I was reading.

The next day, reading Jungle Tales of Tarzan on the school bus, I would chuckle to myself thinking of what would happen if Tarzan were actually to step onto my school bus one day—none of these other military kids would know what to make of him, any more than they knew what to make of me. In contrast to the boring familiarity of the suburban world we lived in, even on Okinawa—a world where it felt like everything was known and repeated ad infinitum—Tarzan’s African jungle world was filled with surprise and savage intensity and a hard-edged consequentiality that I both hungered for and feared. My life was just the opposite. It was like the contents of my brown paper lunch bag, which I knew without having to look— ordinary, unappetizing, and predictable—like my father’s daily hangovers. Moving to Okinawa hadn’t really improved anything. We seemed to bring a trivializing everydayness with us wherever we went. Only in books could I hope to escape it.

Because the truth was that only the imagined world of storytelling felt real to me. It was the only world where everything fit together and made sense, the only place that seemed commensurate to my sense of life’s promise. Compared to my interior identity as Tarzan, my public identity seemed as unsubstantiated and as insubstantial as a rumor, hazy and formless, full of inchoate longing and a sense of vague disappointment. My alternative identity as “Tarzan” might only be available to me through the evocative power of words, but it was reliably there, and as long as I could read and my imagination worked, I could enter that interior world whenever I wanted to. My identification ran so deep, in fact, that it would come as a shock to see my public self by accident in a mirror or reflected in a window.

The charm of Tarzan’s jungle world lay precisely in its darkness and its eruptions of savagery so fierce and deadly that they made the problems of my home life seem entirely negligible. Tarzan HouHous was an irresistible combination of primal instinct, muscular strength, brains, and an elite aristocratic lineage, but what I identified with most of all, I think, was his outsider’s sense of being both wounded and challenged by the fact that he was in a kind of exile from his true home. But where was that exactly? It certainly wasn’t Lord Greystoke’s England because Tarzan didn’t even set foot on English soil until he was well into adulthood. But it wasn’t the African jungle either, any more than Okinawa was my true home. My true home, I had begun to suspect, was nowhere but inside my own head, and in the same way, I reasoned, although the printed pages of a book might have been Tarzan’s place of birth, his true home was also inside my own head. Not where he came from but where he ended up—and where he still remains.

The New York Times Book Review on the CRUSH anthology: find it here